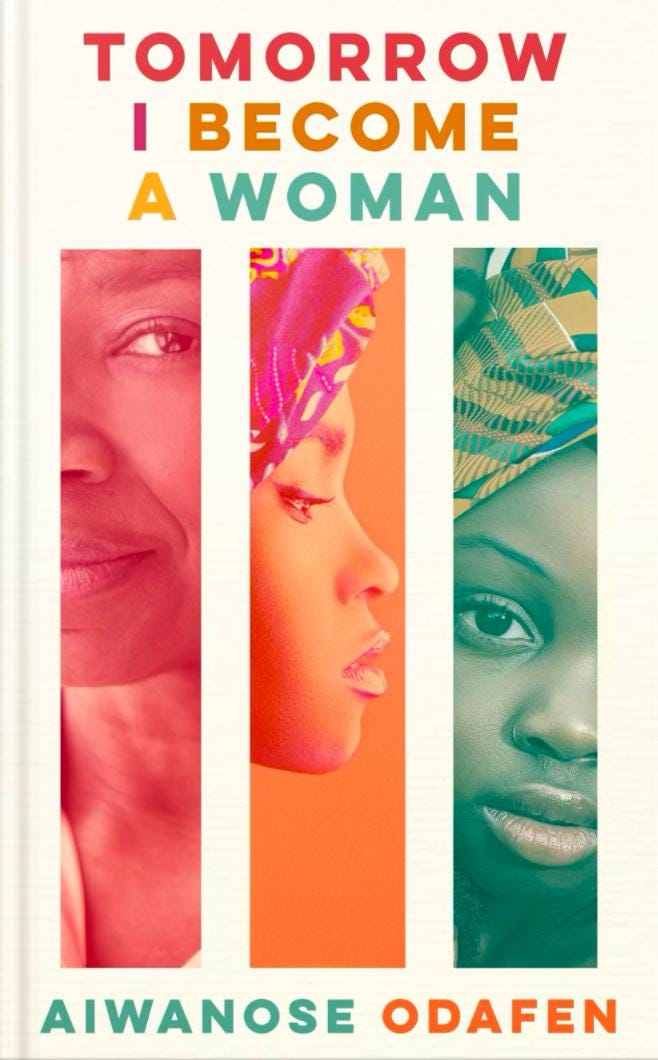

Obianuju, Adaugo and Chinelo are friends studying at the University of Lagos who do nearly everything together. Tomorrow I Become a Woman is the riveting story of their friendship and resilience, set in fast-changing Nigeria between the 1970s and 1990s. The young women learn how to live on their own terms in a traditional society that objectifies women. It’s the author’s debut novel, published in 2022.

“When a woman notices her market is not selling, she has to change what she’s selling.’ I’d laughed then but felt a nagging sense of guilt for finding the hilarity in such words. “Why did we have to change our ‘market’? To mould ourselves like clay, continuously transforming until we were in a form most pleasing.”

Greetings, once again dear reader👋🏽👋🏽

I hope you are doing well and taking good care of yourself.

Welcome to another edition of this spectacular newsletter.

I read this book last August as a book club’s book of the month but the review has taken me a long time to write because it discusses the heavy theme of domestic violence. It is not new or foreign but we can’t stop talking about it.

During her final semester at the university, Uju meets Gozie at church, the best place to find a husband. Her friends had cajoled her to go with them and she indulged them. It did not matter that he was ten years older than her and a tad controlling, her mother approved of him because he was Igbo, Catholic and had a good job. It was a done deal, she was going to marry him. At 21.

Uju’s life as a married woman took a completely different course from anything she could have ever imagined. From the constant questioning about whether or not she was pregnant yet to outright blame for giving birth to girls, there was hardly any breathing space for her. Worse still, most of it came from her mother.

“Uju, you should start trying as soon as you heal,’ Mama said. I stared at her, expressionless.

‘Why are you looking at me like that? Don’t you know your position isn’t safe with only girls? His people might tell him to take another wife. Is that what you want?”

Uju’s mother has to be the worst character of all time. First, she was happy to be rid of her daughter, telling her to be grateful Gozie was marrying her; then she constantly hassled Uju about not being a good wife, even though she (like many other girls) had been groomed for that nearly all her life. Uju’s mother went the extra mile to always take Gozie’s side over her daughter’s, up to telling her brothers not to interfere when they beat Gozie up for beating their sister.

To say Uju suffered would be putting it lightly. From refusing to allow her to get her Master’s degree to questioning her every move, Gozie made sure to show that he was in control. When he was imprisoned, Uju started a small business with money her father gave her. Upon his release, he began to demand for the money from the shop, as per head of the house. The one time she dared to refuse, he beat her purple-and-black. Literally. It was neither the first nor the last time.

When she finally found the courage to leave her husband’s house, she went home. I did not expect much from Uju’s mother but I certainly did not imagine she would ask her daughter if she was sure she wasn’t exaggerating then ask to hear the man’s side of the story. If you ask me, part of Gozie’s confidence was how her had seen Uju’s mother treat and speak to her. Men hardly treat their wives badly when they know they’re loved at home and someone can defend them.

“Mama, what do you want me to say? You’re talking about Gozie. Look at me. Am I not your daughter? See me, see my face, see my hands. Do I look like normal to you? But you’re here talking about Gozie.”

Of course, she went back and stayed there until he nearly killed her. There was nowhere else to go and she had zero support. Her mother had said she could not bring the shame of being a divorced woman to the family. Even if it was made of thorns, a crown was still a crown. How could she, a young woman of 31 with three children, be without a crown on her head?

Mothers should be an ally and a refuge for their children, especially their daughters. There’s no reason on earth to hear or see that someone maltreated your child and you let it slide. If anyone touches my girl, olopa ma ko everybody. During our book club discussion, someone tried to make a case for Uju’s mother that she only taught her daughter what she knew and I was perplexed. That she is/was in an abusive marriage is enough reason to ensure that her daughter does not suffer the same fate. Abi is there something else there? (read this in Yoruba).

While it is easier to shrug and say, “that’s how it is/has always been,” we owe it to our daughters to teach them that there’s a better way. They don’t have to suffer the same things we did, just as we have refused the suffering of our mothers. We must provide a safety net for them and help them to be the best version of themselves. We can’t be quiet about things that matter and keep conforming.

I saw a tweet last week about the narrative that women are incomplete without husbands being a ploy for women to marry foolish men and I couldn’t agree more because why is someone like Gozie anyone’s husband? Small bruise to his ego, he became a monster. He got himself in trouble with his articles, was imprisoned and relieved of his job but somehow, it was Obianuju’s fault.

People who defend rubbish will say it wasn’t his fault that he was the way he was but we all know the truth. Part of Uju’s offences was that she couldn’t give him a son. Who will tell him that it’s what he gave Uju that she nurtured and delivered? The tides eventually turned for Gozie and whatever we saw before was learning work beside his true colour. Worse still, he was appointed a deacon in the church.

One day, we will talk about religious leaders being complicit in this issue of domestic violence but that day is not today. Not Deacon Rapuokwu telling Uju that she’s subject to her husband no matter what and she had to make him feel like a man. Where was Uju’s father in all of this sef?

The highlight of this gripping and thought-provoking story was that Uju eventually realized that she was all her daughters had. The author also explores themes of societal pressure and expectations, self-discovery, and Western influences on traditions.

“What can I do?’ she asked. You can fight, I thought, You can fight for your daughters. But then again, who was I to speak of such things?”

Through Uju’s eyes, we see the complexities of womanhood, identity, tradition, and personal autonomy. Uju and her friends come of age amidst societal expectations. We see the challenges of these young women trying to assert themselves in a society that would not let them speak or make their own decisions. I recommend this book ten times over but I’d definitely need to recover properly before I can read the sequel.

Have you read this book? What did you think about it? Leave a comment, maybe? 😊

#62: Great Fortunes, Great Crimes

“Behind every great fortune lies a great crime.” - Balzac

Five Brown Envelopes follows Nduka “Kaka” Kabiri and his valiant battle to save his father’s company and legacy against mammoth odds. Kaka races against time to pay off a huge debt to avoid the company being liquidated. Driven to the brink of ruin, he bids for a contract, facing off wealthy, powerful, and influential men in the corridors of power.